Feb 10, 2017, 12:00am MST | Angela Gonzales | Senior Reporter, Phoenix Business Journal

Mayo Clinic School of Medicine and Creighton University School of Medicine are preparing to open in the Valley — a move many perceive to be a good sign for addressing the growing physician shortage in Arizona.

But the medical schools’ market entry likely won’t make a dent in the shortage, which is expected to mean the state will have 990 fewer primary care physicians than it needs by 2025.

More medical students does not equal more physicians hanging out their shingles. In fact, Arizona is getting to a point where there will be more students graduating from medical school than there are spots available for them to continue their residency — the additional training in medical settings needed beyond traditional schooling.

It’s that lack of additional training space that’s creating a bottleneck and making the physician shortage worse.

Numerous studies have shown residents who train in a particular city tend to stay there after completing training, which is why it’s crucial to have enough residency slots available for medical school graduates.

President Donald Trump recently acknowledged the national physician shortage, promising to put more doctors into the workforce. But it’s complicated, said Reginald M. Ballantyne III, an industry veteran and owner of RMB III Consultants LLC.

“First, it takes several years following medical school graduation to complete residency training (and perhaps fellowship training in addition) for a physician to engage in active clinical practice,” Ballantyne said. “There is a misconception that expanded and/or new medical schools will result in a quick and timely response to the need that exists for more practicing physicians. It just doesn’t happen that way, and lack of clarity and understanding of this reality can interfere with needed remedial action.”

Medicare provides reimbursement to residency training programs, but funding has been capped for several years, leaving hospitals and medical schools to fund these programs.

That’s not to say groups in Arizona aren’t looking for a way to expand the residency opportunities for medical school graduates. There are several options but as many challenges that will affect the state’s ability to take a bite out of the growing physician shortage.

Collaboration: Schools, hospitals collaborate to expand residency options

Mandatory training doesn’t stop once a student graduates from medical school.

Even though they carry the hard-earned allopathic title of MD or osteopathic title of DO, those fresh medical school graduates still have a few years of residency training remaining, which traditionally is done at a Level I trauma hospital.

PEOPLE ON THE MOVE

Arizona hospitals and medical schools are looking to collaborate in an effort to expand graduate medical education, or GME, training spots.

Last fall, Omaha, Nebraska-based Creighton University School of Medicine signed an affiliation agreement with Maricopa Integrated Health System and Dignity Health that could lead to the development of a four-year medical school in Phoenix.

Dignity has a long-standing partnership with Creighton, hosting third- and fourth-year medical student rotations. With MIHS added to the mix, the GME program at Maricopa Medical Center will be added as well.

“We are going to be taking some of those trainees if we can and they’ll train on the Maricopa campus for part of their training,” said Dr. John Hitt, chief medical officer for MIHS. “The best programs for residents is multi-site.”

By training at multiple sites, residents see different types of patients, gaining a broad educational experience, Hitt said.

Combining expertise within the residency programs at Dignity and MIHS can create synergies and potentially open more slots in a variety of areas, said Dr. Jeffrey Sugimoto, vice president of academic affairs and the designated institutional official at Dignity Health’s St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix.

Banner Health’s $1.2 billion acquisition of the University of Arizona Health Network has the potential to expand GME slots in Arizona. Banner created a new position called chief clinical education officer, promoting Dr. Andreas Theodorou to oversee Banner’s GME programs in Phoenix and Tucson.

This week, Theodorou is seeking approval from the Academic Management Council — created in 2015 as a result of the Banner-UA Health Network merger — to add new residency slots.

“It’s not about an absolute number, but it’s about getting people trained in areas that have a shortage,” he said.

Mayo Medical Schoolhas received more than 3,100 applications, vying for 50 spots, said Dr. Michele Halyard, vice dean of the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine and dean of the Arizona campus.

Funding: Training programs searching for alternative funding sources

Expanding graduate medical education training programs comes with a huge price tag.

The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid provides $15 billion for all programs nationwide, but that funding has been capped since 1997. That means if hospitals want to expand their number of slots, it comes out of the hospitals’ own funds or they need to find alternative funding sources.

Mayo Clinic Scottsdale, for example, only receives funding for 55 residency slots from Medicare, but has 132 residency spots in Arizona, meaning it is funding 77 spots.

“We have quite a bit of investment in medical education here at Mayo,” said Dr. Michele Halyard, vice dean of Mayo Clinic School of Medicine and dean of the Arizona campus.

For years, hospitals and physicians have lobbied Congress unsuccessfully to lift those CMS funding caps.

To make matters worse, Arizona’s residency programs don’t get state funding, either.

With a lack of federal and state funding, hospitals have to be creative in how they finance the expansion of residency slots.

Reginald M. Ballantyne III, a former hospital executive who now is principal of RMB III Consultancy LLC, said there are several funding possibilities.

“One would be to seek establishment of a state/federal partnership not unlike partnerships established for programs such as KidsCare, where states provide initial funding, which is then matched in multiples by the federal government,” Ballantyne said.

Other states have developed creative funding mechanisms that could be considered, said Jay Conyers, CEO and executive director of the Maricopa County Medical Society. For example, California passed a law two years ago requiring insurance companies to subsidize residency programs based on their total enrollment.

None of the local insurance companies responded for comment about this idea.

Maricopa Integrated Health System will use some of the $935 million in bonding from its Proposition 480 passage to create new training sites in its outpatient clinics, giving residents a taste of both hospital and outpatient training experience, said Dr. John Hitt, chief medical officer for MIHS.

“So many of us grew up in a hospital-centric system,” he said. “You have to discipline yourself to say, ‘Actually, isn’t the future of medicine to deliver in the community?’”

Creative Ideas: Scottsdale dermatologist starts his own residency program

For years, Arizona’s health care community looked to expand graduate medical education training in an effort to keep physicians in the state once they complete their residency training.

But it’s costly and takes a concerted effort.

Scottsdale physician Dr. Richard L. Averitte ignored the naysayers and started his own residency training program at his private practice, Affiliated Dermatology.

Averitte started Affiliated Dermatology in Scottsdale about 15 years ago. Five years into his practice, he started looking at a residency program.

It took a lot of phone calls to establish partnerships with Midwestern University and HonorHealth, but now his practice annually takes two new residents who hone their skills before they are allowed to practice on their own.

“We’d like to grow to four eventually,” he said.

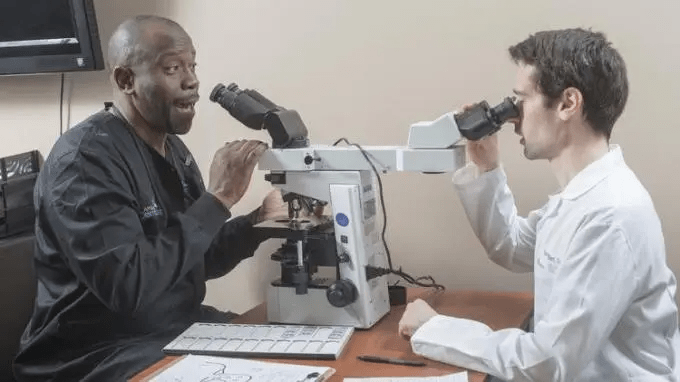

While four doesn’t sound like a big number, it costs from $250,000 to $500,000 a year to run the program, which is a huge commitment from the private practice, which sees upward of 80,000 patients a year across the Valley and has its own in-house pathology and clinical laboratories.

This model can work with other physician specialties. Averitte said he hasn’t run the numbers to see how much he’s spending each year, but he’s about to do that to give other physicians an idea of how much they would need to invest to start their own residency programs.

To entice residents to train in his program, Averitte said he pays residents in the 90th percentile.

“We want folks to come to Arizona and potentially stay here, so we’re trying to be as attractive as possible,” he said.

Jay Conyers, CEO and executive director of the Maricopa County Medical Society, said Averitte is a visionary.

“From Affiliated’s residency program to its in-house pathology and clinical laboratories, he’s built a model

for sustainable growth that will help his team reach the geographic boundaries of our state while also training the dermatologists of tomorrow,” Conyers said.

By following Averitte’s model, other specialty practices could open up to residency programs, Conyers said.

“I hope that when others read about how he’s self-funded a residency program that is preparing young physicians for running their own practices, other physicians will follow suit,” he said. “If others follow suit, it could go a long way toward solving our state’s growing physician shortage.”